Newgrange & Knowth, the Brú na Boínne Tour

Ah, the mighty Newgrange. This Neolithic passage mound stands on the hills of the Boyne, overlooking its river. A place I was lucky enough to visit and take a guided tour of last October during storm Ashley of all days. However, given Ireland’s recent track record with storms, perhaps not all that surprising.

Other than the odd chilly downpour and the wind making it difficult to hear the tour guides, it didn’t detract from the overall experience. An experience I highly recommend to anyone with an appreciation for the great megalithic monuments of Ireland’s ancient past.

Newgrange, approaching from the vistors’ access point

Brú na Boínne Visitors Centre

To see the site, you must book a tour through the visitors’ centre in advance, a detail I missed. You can read more about my first attempt to visit the site, and how it ended in misfortune in my newsletter.

Following the signs for ‘Brú na Boínne’ we found ourselves in the visitors’ carpark, early that Sunday afternoon. After a 5-minute walk we reached the centre, a modern building, which turned out to be a worthy experience alone.

On the first floor, near the entrance there was a wonderful exhibition centre, complete with a life-sized recreation of Newgrange’s entrance. On collecting our tickets, following a good look around the exhibition area, we headed downstairs for lunch in the canteen which offered an excellent selection of food. After a decent meal and a browse around the souvenir shop (also downstairs) which had all the typical items you’d expect, clothes, books, ornaments and jewellery, we exited the building from the ground floor for a two-minute walk to the bus depot. Fortunately, the depot turned out to be a sheltered area dug into the landscape which offered us some protection from the weather.

Five minutes later a bus rolled in to whisk us away, once the previous group departed. In less than ten minutes we reached Knowth, the first of the two sites.

Bridge back to the visitors centre’s ground floor

Knowth

It is well worth mentioning the tour also included a visit to Knowth, an even taller and two centuries older man-made Megalithic mound nearby, which covers only slightly less ground area. The two mounds are similar in that they are surrounded by a ring of horizontal kerbstones, some of which decoratively carved. Unlike Newgrange, Knowth interior is currently inaccessible due to ongoing excavations. However, what makes Knowth unique are the many smaller satellite mounds which surround its great mound. These grassy green mounds have a Tolkienesque quality about them, and make for a marvellous walk even in stormy conditions.

Knowth’s great mound (left) with some of its smaller mounds

Newgrange

After a walk around Knowth it was back on the bus for another short journey to Newgrange, the tour’s main attaction. This site was once surrounded by a wooden henge (a ring of timber uprights). The imprints of the long since rotted posts remain to confirm this.

The site has come a long way from the unrecognisable and overgrown hillock it once was, whose hidden passages were swallowed by the land for millennia, before being rediscovered three centuries ago. Now, reclaimed from the land it stands proud again in all its quartz clad glory as it did eons ago.

Newgrange is a manmade passage mound, constructed using roughly 200,000 tonnes of stone. The exterior is made from sandstone and quartzite, with its core comprising mainly of granite. The site is approximately 13 meters high with a diameter of around 85 meters, which, in terms of ground area covered, makes it Ireland’s largest individual megalithic mound. It is estimated through radio-carbon dating to have been built around 3,200 BC, and taken several decades to complete, which means it is around 5000 years old, even older than Stonehenge or indeed the great Pyramids of Giza.

Symbology

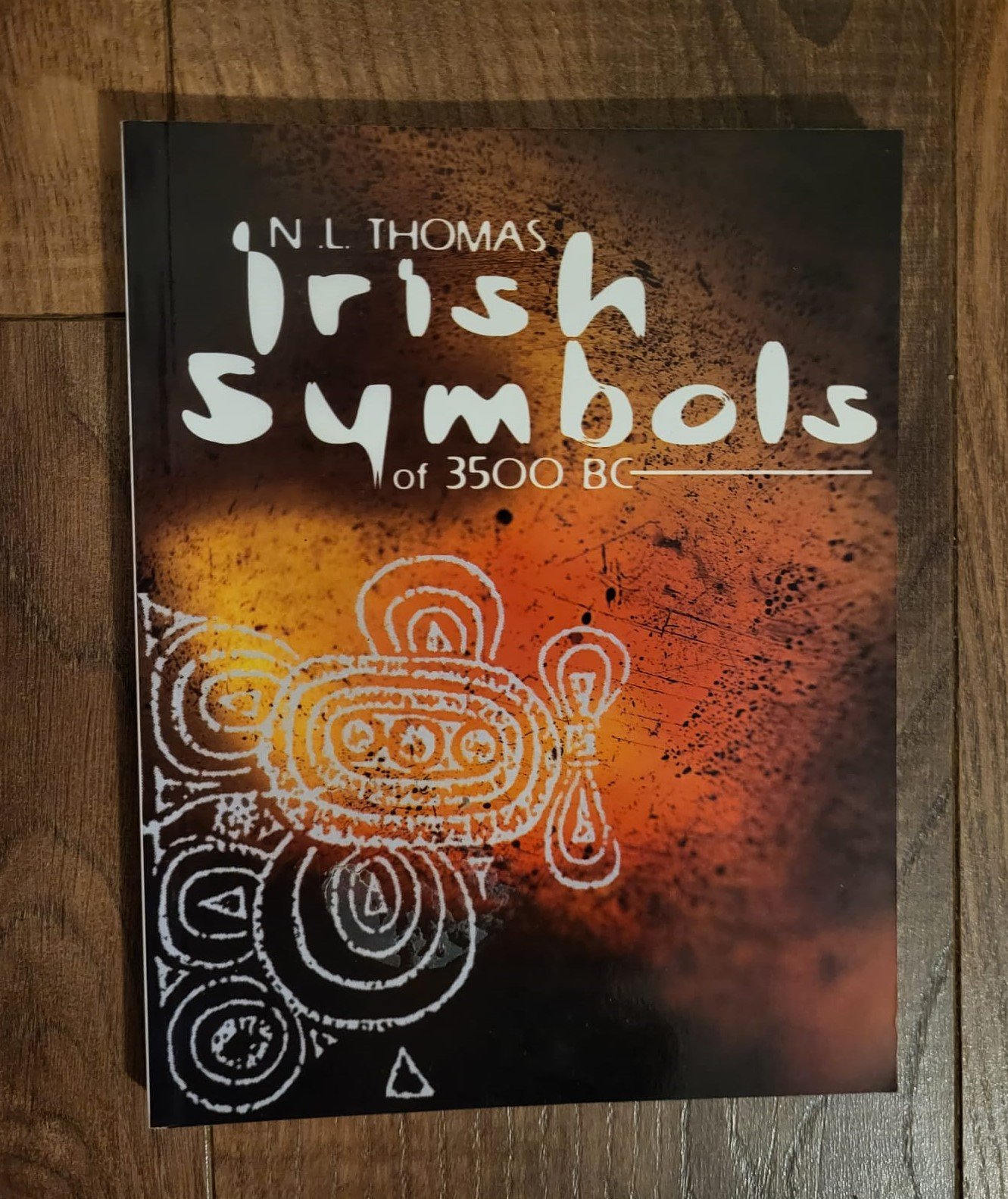

The mound itself is encircled by 97 large kerbstones, many of which carved with intricate spirals. It is speculated by local archaeologists that some of the inscriptions may act as signposts, or an ancient road map of sorts. However, in his book, Irish symbols of 3,500 BC, the researcher N.L Thomas attributes the differing spiral forms as variations of our sun over the seasons, the winter and summer sun, likely acting as part of an early form of calendar.

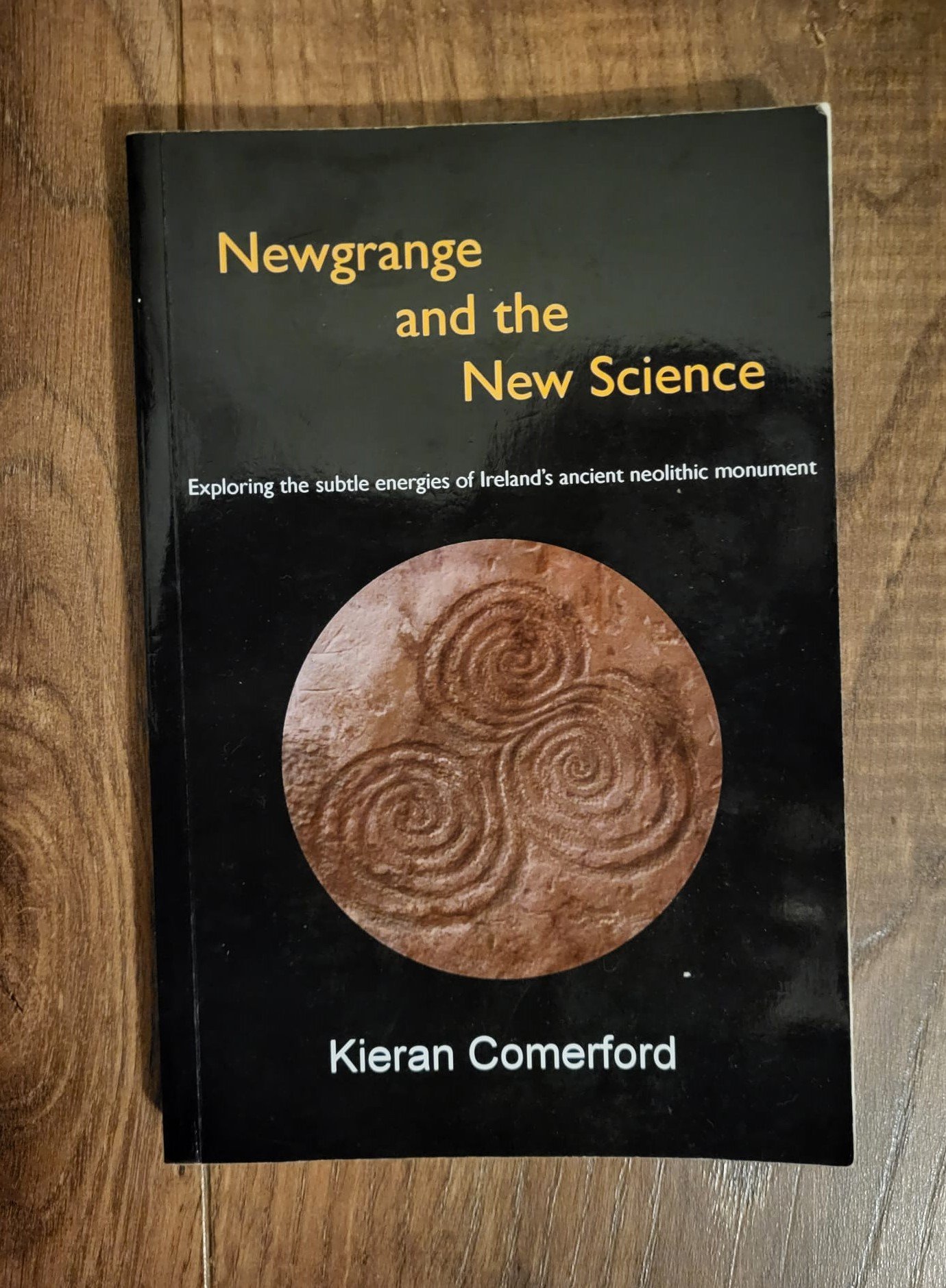

Another less well known, but arguably more intriguing hypothesis is that the spiral represents a place of concentrated energy. Electrical engineer and academic, Kieran Comerford recalls a divining exercise he undertook with a Heritage Awareness Group, at Newgrange. “At a few points on the site we were shown the crossing points of streams which were described as vortices. Here, we were told, the movement of the water in two directions causes a spiralling flow of energy which is detected by a pendulum or by dowsing rods. This was my first explanation of a possible meaning of the Newgrange spiral, a point of energy concentration.” You can read more about this and other spiral theories he has heard put forward in his book, ‘Newgrange and the New Science’.

At this point I think it only right I hold up my hand and admit these spiral theories helped influence some of the more supernatural and mystical elements of the storyline in my ‘Deep Waters’ novel.

Spiral Symbol Resources

Further resources to interpret the Brú na Boínne’s symbols

Entering Newgrange Mound

Before entering Newgrange, our guide instructed us to carry any bags we might have in front of ourselves, and to avoid touching the surfaces to help preserve the site.

Inside, a 19-meter-long passage runs towards the heart of the mound, with two much shorter passages near its end, taking on a crucible form. There are large basin-like stones in each of these sections, whose hollowed surfaces were found to contain the cremated remains of many Neolithic peoples.

Newgrange’s entrance kerb stone with its many spirals

Ancient Farmers & God-Kings

Archaeologists postulate the charred remains belonged to those who held the highest-ranking positions in the community, most likely the rulers of the time. The unburnt skeletal remains of a man belonging to this era were also recovered and DNA tests carried out on part of his ear bone returned inbreeding in its results. This was a practice typically associated with the God-King family dynasties of ancient Egypt among other ancient civilisations.

We know very little about the people who built these Neolithic passage mounds since they belong to a time before the writer word. What we can assume from the time and effort they invested in constructing these great structures, is that they were settled, so likely Ireland’s first farmers, rather than hunter-gatherers. They also had a social hierarchy, with a ruling class hinging on a set of supernatural beliefs based on local weather patterns, the changing seasons as means of explaining nature, and their environment, the physical world they occupied. The gods they worshipped, like many other ancient cultures inspired by celestial bodies, be they the sun, the earth, or the moon.

Newgrange and the Winter Solstice

However, this sacred site is so much more than just a burial site, it is a place where themes of birth and life are just as prevalent as death. In fact, Newgrange can be viewed as the pinnacle of a dry-stone construction technology spreading across Ireland from the west, over several centuries.

The positioning of a roof box, a separate rectangular opening above the entrance, shows the builders had an acute understanding of the sun’s positioning throughout the year. So much so, that the roof box is positioned in a way which allows the whole passage chamber to light up over a 17 minute period at the morning sunrise of the shortest day of the year, the winter solstice.

After hearing accounts of this phenomenon from local visitors to the site Professor Michael O’Kelly, one of the most renowned archaeologists in modern times to examine the site, documented his own experience of the solstice illumination.

On the 21st of December 1967, he stood alone at the end of the passage waiting and wondering, what, if anything might happen. To his astonishment, a finger of light from the rising sun slipped through the lightbox spreading deeper into the passage and growing across its floor and up on to its walls with each passing minute.

He later wrote this about the growing shaft of light he had witnessed in the mound’s chamber that winter solstice,

"lighting up everything as it came until the whole chamber - side recesses, floor and roof six metres above the floor - were all clearly illuminated"

At one point he claims he was so overwhelmed with what he saw that morning that a part of him feared the Dagda, a powerful pagan god long associated with the site might also enter amongst the sun’s beams and bring the mound’s roof crashing down atop of him.

A Place of Fertility & Life

Some historians speculate that the spear of light penetrating the mound, was meant to signify fertility by its builders, and the moment of conception. The entrance of the mound representing an earthly womb.

So, every winter soltice, the sun god’s shaft of light impregnates the earth goddess’s womb, resulting in the birth of a new year.

Simultated Winter Solstice

The Bru na Boinne tour, offers a simulated, sped-up version of this experience using artificial light, which I along with the rest of my group standing at the end of the chamber were lucky enough to experience. Our guide delivered a profound monologue on the significance of this event to its builders as she slowly dialled the light up the corridor much to our delight.

To witness the real thing one must enter a lottery and hope their number is someday drawn, however despite the ingenuity of the original builders, even if you are lucky enough to be chosen, given the Irish weather, especially at this time of the year, there is every possibility that the sun may be hidden behind a veil of cloud that day, which makes this tour a reasonable substitute to the annual event.

Myths & Legends

Newgrange has its fair share of myths and legends and its lore is referenced more than any other ancient Irish structure in early manuscripts, unsurprisingly for a site of such magnitude and importance.

It has long been associated with the Tuatha de Danna, a divine race, whom according to the book of invasions, took up residency in Ireland after travelling there in a sky ship. This saga belongs to one of the earliest collections of Irish mythology penned by an anonymous medieval author.

The Dagda

One of the Tuatha de Danna’s most potent members, the Dagda, meaning the good god, in this case good, as in great or powerful, and yes, the same deity Professor O’Kelly momentarily feared encountering during his winter solstice stay, appears in several Newgrange tales.

According to local legend, Newgrange belonged to the druid Elcamar who lived there with his beautiful wife, Boann, the goddess incarnate of the river Boyne. Brú in Gaelic means palace, so Brú na Boínne translates as ‘the palace of the Boyne’. Unfortunately, when the Dagda visits the site and sets eyes on Boann, he’s struck with lustful thoughts. Unable (or unwilling) to resist them, he soon sends Elcamar on far off errands.

While Elcamar is away, Dagda seduces and impregnates the lush Boann. To disguise his roguish misdeed, the wily Dagda uses magic powers to prevent the sun’s movement for 9 months, creating the impression that only a single day has passed. In the meantime, he keeps Elcamar occupied. His great powers preventing the druid from knowing thirst, sleep or hunger until such time as Boann has given birth to the Dagda’s son, Aongas Óg, meaning Aongas the young, since seemingly only a day has passed.

Aongas Óg

It’s at this point that Dagda takes possession of the Newgrange while Elcamar is left wandering the land. Aongas, the love child of Dagda and Boann, becomes synonymous with love. However, as Aongas grows older and learns his father has no plans to leave him Newgrange, he asks if he can have ownership of the place for a single day and night, to which Dagda agrees. Afterwards, Aongas argues that since eternity itself comprises only of days and nights, he now owns the site forever, which the Dagda reluctantly accepts.

Another account of Aongas, is his swan tale, a popular theme in Irish mythology where he falls in love with a Caer, a young earthly woman who is transformed into a swan by magic. In this story when he touches her in this form, he too becomes a swan and together they fly to the banks of Boyne, where they still reside, and even to this day the occasional lucky passer-by may catch their serenade, or so I’ve heard.

In the Fianna cycles, a much later collection of Irish myths, Aongas is said to have brought the body of the dead Diarmuid, a former Fianna warrior, to Newgrange to breathe new life into it. That tales of Aongas transcend ‘the book of invasions’ to the Fianna collection demonstrates his enduring presence at Newgrange in local lore.

Lugh, Cú Chulainn & other legends

Other figures from Irish mythology connected to the site are Lugh, and his son, the warrior god, Setanta, better known as Cú Chulainn. Lugh is also part of the Tuatha de Danna and another great Irish god. One of the more popular accounts of Setanta’s birth is that he was immaculately conceived in Newgrange when Lugh, using his magic transfers a child into the womb of Diechtine, the daughter of a famous charioteer, to make up for the baby she had recently lost. The theme of this tale supports the concept of Newgrange as a place of birth and life, as opposed to just a tomb, as later revisionists might have us believe.

Generational stories of kings who sent their sons to stay and fast in Newgrange for several days and nights, for future prosperity also abound the site.

Fun fact

Both passage mounds have been vandalised with scrawling over the years, but the earliest graffiti which can be found is in Ogham, a now long extinct language, and Ireland’s earliest writing form. The language comprises of linear scratch types thought by historians to date back as far as the 4th century.

Newgrange entrance, a chilly wait outside